Your Risk-Free Bias Isn’t Keeping the Kids Safe

But it is no good for parents everywhere.

Even before the pandemic (remember then?), the pressure to protect the kids from all possible dangers has moved to the front and center for parents, especially in the U.S. “There used to be more of a natural growth philosophy,” says Elizabeth McClintock, a sociologist at the University of Notre Dame. “If you just let kids play, they’ll grow and it'll turn out okay.”

Now? Judgment from outsiders means getting unsolicited advice or chastised for not following another parent’s preferences. Sometimes the consequences are more dire. Some parents have gotten the cops called on them for taking calculated risks, such as leaving their child in the car while they run into a pharmacy to get diapers. “It’s an emotional burden,” says McClintock. Not only are parents stressed by the pressure they put on themselves to raise happy and successful kids, but they’re also constantly being told they’re doing it wrong.

McClintock and her graduate student Abigail Jorgensen — who are both moms themselves — launched a study to look into how parents are policed for taking not-so-risky risks. They talk about how parents’ views of risks have changed for the worst and how bystanders’ perceptions of “risky” parenting can lead to legal consequences.

How has the way that parents think about risks changed over recent years?

McClintock: The U.S. as a whole has become more preoccupied with risk and risk reduction. Even in situations where the actual risk of something hasn't changed over recent decades, the perception of that risk has changed. A good example of that might be kidnapping — the risk of a child getting kidnapped has not moved much. But parents’ fears around it have. I’m the first person to admit I won’t let my kid out of my sight. But I'm also aware that on some level it's irrational because the risk isn’t that big.

Why are parents becoming more wary even when risks haven't shifted?

McClintock: Part of it is probably the availability heuristic. When you read something in the news, it's really easy to imagine that happening. It’s accessible to your imagination. We're all plugged into our computers. If something horrific happens to a child, we all hear about it. And we all imagine that could be our child next. On some level, it could. But the risk of that really hasn't changed. People are just queued into this information.

Jorgensen: What's really interesting to me is that it's happening in the U.S. and not necessarily in other contexts. My husband is from Denmark, and it's very common in Denmark to leave your child in a stroller outside the restaurant while you go in and eat. Someone from Denmark got arrested in New York City for doing exactly that. Presumably, everybody in Denmark has access to the same news stories and is hearing the same horrific things that are happening to kids, but the U.S. has responded to kidnapping with really strong norms around parenting and Denmark hasn’t.

How do parents today approach risk reduction?

McClintock: There’s this increasing expectation that parents are supposed to search for information and use that information to monitor and reduce risks to their kids. That can be unhealthy when parents decide they're going to play doctor with their kids, like with deciding on their own that vaccines are too dangerous. But it also speaks to this increasing doctrine of intensive parenting, which is that you're supposed to be doing all this work on behalf of your kid: managing all parts of their life, maximizing their opportunities, reducing their risk.

Jorgensen: Those tasks — gathering information, deciding on the best course of action, and measuring whether that course of action was right — disproportionately fall to women.

What sort of burden does this put on mothers?

McClintock: It's huge. You’re spending a lot of time researching what should I be feeding them? When should they get vaccinations? Should they go to daycare or should I get a nanny? The responsibility of raising a child disproportionately falls on women, even as that responsibility is getting ratcheted up.

Jorgensen: It's not just the burden of trying to make these decisions, which is huge in and of itself. It's the emotional burden of dealing with how people around you react. It's not just that I'm deciding whether or not to get my daughter the new COVID vaccine whenever it comes out. It's that I'm deciding that, and I'm going to have family, friends, and social media acquaintances giving me feedback on whether they think that idea was right or not. In some situations, it's not just feedback. It's about people calling the police on mothers who leave their children in a car or at a playground.

McClintock: When I was pregnant, people would come up and ask invasive questions. Someone in the gym asked me about my plans for childbirth — someone I had never met. I had my dentist do something similar. And I had strangers ask me if I was planning to breastfeed. People are very willing to intervene, whether it's by calling the police or just expressing their opinion in an inappropriate way.

Jorgensen: It’s a ubiquitous experience that pregnant people get judged for their choices during pregnancy. We both got comments that our spouses certainly didn't.

You brought up that some bystanders call the police on parents who leave their kids at playgrounds or in cars. How often does that happen?

Jorgensen: I was home-educated until I went to college, and I'm still tapped into a lot of those circles. I heard this story going around about people calling the police on you if you leave your kid in a car when you run into the store. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized there is a lot of criminalization of parents, and there is a pattern to it. For example, women are being criminalized for their parenting choices more than men. Is that because women tend to spend more time with kids than men do, and therefore they have more opportunities to be criminalized? I don't know. Is it because people judge women harsher than men? I don't know. That was where the idea for our study germinated: What impacts how someone's going to respond to you leaving your child in what could be considered a risky situation?

McClintock: In all these cases we found, there wasn't an obvious risk. The moms were doing this in weather in which the kid wasn't going to get overheated or overly cold. The mom was child-locking the kid in the car. And the mom wasn't gone very long. Yet women are getting policed anyway for neglectful parenting.

Jorgensen: The other day I went into the donut store, and I had my five-month-old daughter with me. I thought about leaving her in the car. It was a mild day out. I could crack the windows, and I wouldn't be in there for more than five minutes. But the thing that made me get her out immediately was thinking somebody could see her and call the police. The risk that you're evaluating as a parent isn't just coming from the decision you make. It’s coming from the way that other people are going to respond to that decision.

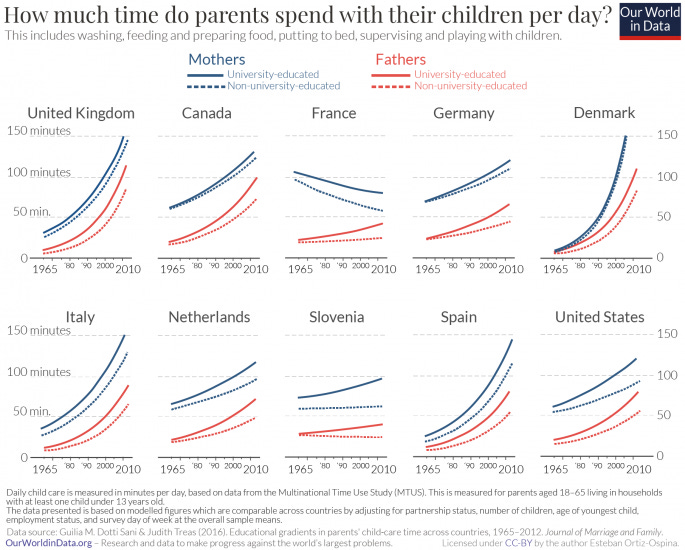

Bonus Contenu: Moms Spend More Time with the Kids

A survey of 10 countries has found that mothers universally spend more time with their children than dads do. Only in France is that division becoming more equitable. For both moms and dads, time spent with kids is on the rise — even as more moms take jobs outside the home.